This is a searchable page for all things ACCT 2001 at UConn - Storrs! It is organized by chapter, with additional lists of questions for specific exam review documents. You can simply look at the questions in a particular chapter as you are studying the chapter, or come here when you are stuck on a particular problem/topic.

Don't see what you're looking for? Please send us your question using the FAQ Form below!

General Questions

Honors Conversion: ACCT 2001 is a 2000-level course, it is nonetheless an introductory course. Therefore, the rigor is not suited for honors credit. In the accounting department, honors credit is generally considered at the 3- and 4000-level.

Chapter 1 – Business Decisions and Financial Accounting

What is the difference between financial accounting and management accounting?

Financial accounting has its focus on the financial statements which are distributed to stockholders, lenders, financial analysts, and others outside of the company. Courses in financial accounting cover the generally accepted accounting principles which must be followed when reporting the results of a corporation's past transactions on its balance sheet, income statement, statement of cash flows, and statement of changes in stockholders' equity.

Managerial accounting has its focus on providing information within the company so that its management can operate the company more effectively. Managerial accounting and cost accounting also provide instructions on computing the cost of products at a manufacturing enterprise. These costs will then be used in the external financial statements. In addition to cost systems for manufacturers, courses in managerial accounting will include topics such as cost behavior, break-even point, profit planning, operational budgeting, capital budgeting, relevant costs for decision making, activity based costing, and standard costing.

Does 'on account' means the same thing as 'on credit'?

Yes, "on account," "on credit," and "with credit" all mean the same thing; that whatever is being purchased or sold is going to be paid for in the future.

What is retained earnings?

Generally, retained earnings is a corporation's cumulative earnings since the corporation was formed minus the dividends it has declared since it began. In other words, retained earnings represents the corporation's cumulative earnings that have not been distributed to its stockholders. The amount of retained earnings as of a balance sheet's date is reported as a separate line item in the stockholders' equity section of the balance sheet.

How do I calculate the "change in cash" for PA1-2, part 2?

This is company's first year in business, so their beginning cash balance is zero. Their end-of-year balance is therefore the change in cash.

Why does Connect keep saying my PA1-1,2 answer is incomplete?

If you have completed assigned problem CP1-1,2 but it says your answer is incomplete, you are most likely missing the dates on the financial statements! Please see exhibit 1..7 in Chapter 1 for examples of how the dates should be formatted at the top of each financial statement.

Chapter 2 – The Balance Sheet

UGH! How do I remember which accounts have debits and which accounts have credits?

At this point, it is not uncommon for students to be struggling with memorizing the debit/credit rules and understanding T-accounts. However, it is imperative to this class that you gain an understanding of debits and credits, and which accounts have normal debit balances and which accounts have normal credit balances. To that end, I found two excellent videos that might help. Both take a slightly different perspective, but both are right on!

Why is the order in which assets are reported on the balance sheet based on when the assets are expected to be used or to turned into cash but not paid for?

The balance sheet lists assets in descending order of liquidity (how quickly the asset can be converted to cash), with the most liquid assets listed first. Assets, by definition, are things that have already been paid for. If they are not actually cash or something like Accounts Receivable which will eventually be cash, they are generally listed in the order in which they will be consumed.

- Cash is the most liquid of assets.

- Accounts receivable are what customers owe the company for products or services delivered on credit. Accounts receivable are less liquid than cash, but are expected to be collected within 30 to 60 days.

- Inventory is product for sale and is generally the next liquid asset because it is expected to be sold and converted to cash within one year.

- Finally, prepaid expenses are those expenses that are already paid for future services not yet received. Typical prepaid expenses are prepaid insurance and prepaid rent. Prepaid expenses are assets because they represent cash payments already made for services not yet received.

- Following the current assets are the non-current assets. Non-current assets are also listed in order of liquidity. For example, fixed assets include office equipment, furniture, vehicles, machinery, buildings, and even land. Fixed assets are productive assets that are not intended for sale, but are used to support the production or the sale of product or services.

Why is the order in which liabilities are reported on the balance sheet is based on when the liability is expected to be paid or settled?

Yes, liabilities are reported on the balance sheets based on when they are expected to be paid. Like assets, liabilities are divided into two broad categories on the accounting balance sheet: current liabilities and non-current liabilities. Current Liabilities, or short-term liabilities, are those liabilities that are expected to be paid within one year. Examples are accounts payable, current portions of long-term debt, and short term notes payable. Accounts Payable represents a short-term debt mainly from the purchase of inventory. Accounts payable may also include the purchase of goods, services, and supplies on credit. Long-Term Liabilities are not expected to be paid within a year. Examples are long-term notes such as a mortgage or lease.

What is the difference between 'purchased' and 'paid'?

Purchased means that the company bought something, but hasn't necessarily paid for it yet. "Purchased" in a sentence, for our purposes, must then be followed by "on account," meaning they plan to pay cash for it in the future, or by "for cash" or "in cash," meaning they paid for it at the same time as they purchased it.

Generally, if the problem says "paid," it means that they are paying for something with cash. It can either be something they just purchased "purchased equipment and paid for it in cash" or it can be something they purchased in the past "paid for the equipment they purchased last month."

What is the difference between accounts payable and notes payable?

While both of these are liabilities, Notes Payable involves a written promissory note. For example, if your company wishes to borrow $100,000 from its bank, the bank will require company officers to sign a formal loan agreement before the bank provides the money. Perhaps the loan paperwork will be a half inch high. Your company will record this loan in its general ledger account, Notes Payable. (The bank will record the loan in its general ledger account Notes Receivable.)

Contrast the bank loan with phoning one of your company's suppliers and asking for a delivery of products or supplies. On the next day the products arrive and you sign the delivery receipt. A few days later your company receives an invoice from the supplier and it states that the payment for the products is due in 30 days. This transaction did not involve a promissory note. As a result, this transaction is recorded in your company's general ledger account Accounts Payable. The supplier will record the transaction with a debit to its asset account Accounts Receivable (and a credit to its account Sales).

Where do dividends appear on the financial statements?

Dividends are reported on the statement of changes in retained earnings. The dividends declared and paid by a corporation are also reported as a use of cash in the financing section of the statement of cash flows. Dividends are not reported on the income statement since they are not expenses. Since the balance sheet reports only the ending account balances at an instant of time, the Cash and Retained Earnings amounts reflect the balances after dividends and other transactions.

Chapter 3 – The Income Statement

Question on E3-6: With regard to letter c, The city of Omaha hired Waste Management, Inc., to provide trash collection services beginning January 1. The city paid $12 million for the entire year. How one would write this as a journal entry?

From the city's standpoint, they have just prepaid Waste Management, Inc., $12 million to provide them with future services. They have to record that their cash balance has been reduced by $12 million, and in addition, they have a claim on services from Waste Management. The entry would be:

(dr) Prepaid trash collection services 12,000,000

(cr) Cash 12,000,000

Incidentally, from the perspective of Waste Management, they have received $12 million in cash and they OWE that same value in trash collection services to the city of Omaha. They would record this transaction as:

(dr) Cash 12,000,000

(cr) Unearned trash collection revenue 12,000,000 (this account is a liability)

Is unearned revenue considered a revenue?

No, unearned revenue is a liability, and belongs on the Balance Sheet (not the Income Statement). Unearned revenue means that you have received compensation for a service or product that you have not performed or provided yet, so you owe the service/product to them (therefore, it is a liability).

When the owed service is performed or the product is provided, you will debit unearned revenue (to decrease the liability) and credit revenue, because the service has been done, therefore the revenue is now earned.

Practice Exam 1, Chapters 1, 2 and 3

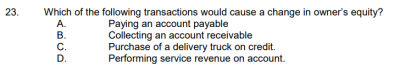

#23 - Why would performing service revenue on account cause a change in owner's equity? and by extension, why wouldn't the other options as well.

Owner's equity only changes if you increase or decrease revenues, expenses, retained earnings, dividends or a stock account.

- The entry to pay an account payable involves a decrease to A/P (debt a liability) and a decrease to cash (credit an asset).

- The entry to collect an account receivable involves an increase to cash (debit an asset) and a decrease to accounts receivable (credit an asset).

- The purchase of a delivery truck on credit involves an increase to the trucks account (debit an asset) and an increase to accounts payable (credit a liability).

- When you perform any service, you have earned the revenue, regardless of when the customer pays you. You need to record the revenue with a credit (increase) to the revenue account, which in turn increases retained earnings and owners' equity. You would debit (increase) accounts receivable for the same amount, as you want to show on your balance sheet that someone owes you money. This part of the entry increases total assets.

Chapter 4 – Adjustments, Financial Statements, and Financial Results

What is the accrual basis of accounting?

Under the accrual basis of accounting, revenues are reported on the income statement when they are earned. (Under the cash basis of accounting, revenues are reported on the income statement when the cash is received.) Under the accrual basis of accounting, expenses are matched with the related revenues and/or are reported when the expense occurs, not when the cash is paid. The result of accrual accounting is an income statement that better measures the profitability of a company during a specific time period.

For example, if I begin an accounting service in December and provide $10,000 of accounting services in December, but don't receive any of the money from the clients until January, there will be a difference in the income statements for December and January under the accrual and cash bases of accounting. Under the accrual basis, my income statements will show $10,000 of revenues in December and none of those services will be reported as revenues in January. Under the cash basis, my December income statement will show no revenues. Instead, the December services will be reported as January revenues under the cash method.

There will be a difference on the balance sheet, too. Under the accrual basis, the December balance sheet will report accounts receivable of $10,000 and the estimated true profit will be added to owner's equity or retained earnings. Under the cash basis, the $10,000 of accounts receivable will not be reported as an asset, and the true profit will not be included in owner's equity or retained earnings.

To illustrate a difference in expenses, we will assume that the heat and light expense that I used in my accounting service is metered by the utility on the last day of the month. The utilities that I used in December will appear on a bill that I receive in January and will pay on February 1. Under the accrual basis of accounting, the utilities that I used in December will be estimated and will be reported as an expense and a liability on the December financial statements. Under the cash basis of accounting, the utilities used in December will be recorded as an expense on February 1, when the utility bills are paid.

For financial statements prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles, the accrual method is required because of the matching principle.

What are accrued expenses and when are they recorded?

Accrued expenses are expenses that have occurred but are not yet recorded through the normal processing of transactions. Since these expenses are not yet in the accountant's general ledger, they will not appear on the financial statements unless an adjusting entry is entered prior to the preparation of the financial statements.

Here is an example. A company borrowed $200,000 on December 1. The agreement requires that the $200,000 be repaid on February 28 along with $6,000 of interest for the three months of December through February. As of December 31 the company will not have an invoice or payment for the interest that the company is incurring. (The reason is that all of the interest will be due on February 28.) Without an adjusting entry to accrue the interest expense that the company has incurred in December, the company's financial statements as of December 31 will not be reporting the $2,000 of interest (one-third of the $6,000) that the company has incurred in December. In order for the financial statements to be correct on the accrual basis of accounting, the accountant needs to record an adjusting entry dated as of December 31. The adjusting entry will consist of a debit of $2,000 to Interest Expense (an income statement account) and a credit of $2,000 to Interest Payable (a balance sheet account).

Is the depreciation expense account separate for each asset that depreciates? Or do you accumulate all depreciation expenses in one account? For example, would the depreciation expense for a period include the depreciation of equipment and a vehicle, such that the depreciation expense for a single year could differ from the accumulated depreciation of one asset for a single year?

For purposes of this class (because it gets more complicated in ACCT 3201), yes, each individual asset (or category of assets, like "trucks") has it's own separate accumulated depreciation and depreciation expense account. So the accumulated depreciation account for equipment would equal all of the depreciation expense taken over the life of the asset (all years) and the depreciation expense account for a particular year would only include the amount of depreciation expense taken in that year.

I don't understand closing entries!

Remember that the point of closing entries is to bring all the revenue, expense and dividends accounts to zero. There are two journal entries.

1) you debit all of the revenue accounts in the amount of their ending balances. Now they are zero. Then, you credit all of the expense accounts in the amount of their balances. Now they are zero, and you have an unbalanced journal entry, because your debits (revenues) don't equal your credits (expenses). The difference is either a net income or a net loss. Net income, if your revenues exceeded your expenses. Net loss, if your expenses exceeded your revenues. So, you either credit the difference to retained earnings (net income), or you debit the difference to retained earnings (net loss). For example:

dr revenues 100

cr expenses 80

cr retained earnings 20 Here, you have a net income.

dr revenues 80

dr retained earnings 20 Here, you have a net loss.

cr expenses 100

2) you have to close out dividends. Since dividends has a normal debit balance, you credit it in the amount of it's ending balance, in order to bring it down to zero. You then debit retained earnings for the same amount. This makes sense, because dividends reduces retained earnings.

So, in the first entry, you've transferred the amount earned by the company to the company's owners. In the second entry, you've reduced the amount belonging to the company's owners by the amount that they withdrew.

Now, all of your temporary accounts have zero balances, and the retained earnings account is equal to the ending balance reported on the balance sheet.

Why do we use the previous year's retained earnings balance on an unadjusted balance sheet for the current year?

This is because until we do our closing entries, retained earnings has not been adjusted for current year activity. For purposes of this class, the ONLY time we EVER make an entry to the retained earnings account is when we post the closing entries. So there is no reason for that balance to change throughout the year. Only the Post-Closing trial balance will show retained earnings at it's official ending balance.

When making closing entries on the second page of the worksheet, you put Retained earning 8,000. I am a little confused about how you get the 8,000 because I consider 8000 as net income which is calculated by Revenue minus Expenses.

What you are looking at is the first of the two closing journal entries.

Yes, the $8,000 represents the company's net income. It is the difference between the revenue we are debiting and the expenses we are crediting. We are closing net income to retained earnings, so we are crediting retained earnings for the amount of net income earned during the year. There is no account named "net income." Net income is part of retained earnings. Put another way, we are transferring the values of all of the revenue and expense accounts into retained earnings. The net of those accounts is $8,000, which is also equal to net income.

Chapter 5 – Fraud, Internal Control, and Cash

“Enclosed with the bank statement received by June company at August 31st was an NSF check for $930. No entry has yet to been made by the company to reflect the bank action in charging back NSF. In making correcting journal entries based on bank reconciliation. NSF check will result in an entry on Junes book with a…” Here I can not tell if the NSF check was sent out by them or was received by the customer.

The NSF check is something that was received by the company from a customer. The company deposited it. When the check was presented to the customer's bank, the customer's bank refused to honor it because the customer didn't have enough money in their account. So the bank is letting the company know that the customer's check was bad, and the company has to subtract those funds from their cash balance.

When the company originally deposited the check, they would have debited cash and credited accounts receivable. Since the check wasn't good, they have to reverse this entry. Therefore, they debit accounts receivable and credit cash. This has the effect of re-establishing the customer's balance on the company's books and reducing the cash balance for the amount that, it turns out, was not deposited.

"After doing a bank reconciliation, a note receivable [collected] by the bank should be entered in depositors accounting records by a…” I could not tell if the company was paying the bank or if it was the companies money.

It is the company's money. The note receivable is being collected by the bank, as a service to the company, and depositing it in the company's account.

In the textbook, it shows that the adjusting journal entry for understating a payment to somebody (page 231) is a debit to Accounts Payable, and credit to cash-- this makes sense, but what would the journal entry (if any) be for the opposite case, when the payment is overstated?

Yes, exactly. If the actual check was written for $56 but the company recorded it as $65, they would have to debit cash for $9 and credit accounts payable for the same amount to correct the original entry.

Regarding this question:

The reason the answer is A is because the bank collected the note receivable for you and deposited it in your account. So your cash balance increased. Increases to a cash account are recorded with a debit to cash.

Chapter 6 – Merchandising Operations and The Multistep Income Statement

Comprehensive problem C6-1, regarding the trouble students may have calculating CGS and the customer payment on the bonus problem:

You have a certain number of shirts on hand (the number BSS bought minus the number they returned). You are selling exactly the same number of shirts that you bought, so the cost of the shirts is exactly what you have in inventory.

You can just look at your journal entries to get your inventory balance.:

October 10: + amount paid for the purchase

October 11: - amount credited by the seller for the return

October 12: - amount credited by the seller for the allowance

October 13: - amount taken for the discount.

- Thus, your shirts have a cost equal to the balance in inventory. That's what you book for CGS.

- The return on the sale is half of the sale and half of the CGS.

- The allowance is on the remaining number of shirts (half of the original amount).

- The amount they pay you is the (original price, minus the return, minus the allowance), minus the discount on the sum in parenthesis.

I was going over one of the chapter 6 problems that we did in class. According to the uploaded notes, from the sellers perspective under FOB destination, shipping expenses aren't subtracted to get net sales. they seem to be disregarded entirely. Why is this?

Shipping costs to the purchaser are a selling expense, included in operating expenses. Think of it in these terms: offering free shipping is a marketing tool to get a customer to commit to the sale. Marketing is part of operating expenses.

C6-1 Why is it that BSS could take the discount when they pay on October 13th, even though the order was placed on October 1st?

Remember that placing the order is not a recordable transaction. The purchase hasn't actually occurred until the shirts are delivered to BSS. Therefore, the date of the purchase is October 10th and when they pay for them it's only been 3 days. Even if the sale was FOB shipping point (the problem doesn't say), that only means that we pay for shipping. The goods don't actually get recorded until received by BSS.

What should fall under operating expenses?

Everything except cost of goods sold, which includes freight (or transportation) in.

I am trying to understand the concept of shrinkage; I know it is calculated by subtracting the cost of inventory counted from the amount in the perpetual inventory system though is shrinkage recorded as a credit to inventory or as an expense?

Actually, both. This is called a "book-to-physical" adjusting entry which reduces the inventory account by amount of the shrinkage and increases Cost of Goods Sold (the expense of inventory) by the same amount. Therefore, you debit Cost of Goods Sold and credit Inventory.

Practice Exam 2, Chapters 4, 5 and 6

Number 14 on the practice exam, why is the answer A and not D? The equipment was used for one year and 9 months. The one year would be 3,000 and the nine months would be 2,250 so for the full year and nine months the depreciation is 5,250 at the end of December 31, 2017. And since it's an expense wouldn't it be debited as 5,250 depreciation expense?

Depreciation expanse always represents ONLY the 12 months of expense for that given year. The $2,250 represents the depreciation on the equipment for 2016. The question is asking for the adjusting entry for 2017. Notice that the accumulated depreciation balance is $2,250. That is because in 2016, the company's year-end adjusting entry was for nine months of the year, as follows.

Depreciation Expense 2,250

Accumulated Depreciation 2,250

So in 2017, we've had the equipment for a full year, so we need to record 12 months of expense:

Depreciation Expense 3,000

Accumulated Depreciation 3,000

Now the ending balance in accumulated depreciation will be $5,520, representing a full year and nine months.

We will never book more than 12 months of depreciation expense in a year. If we did, our depreciation expense would be overstated for the year. If we had, in fact, not booked the expense last year, it would have to be booked as a prior year adjustment, which causes ALL SORTS of accounting issues which you don't even want to think about right now! 🙂

Practice Exam 2 Question 7, "While preparing a bank reconciliation, an accountant discovered that a $327 check was returned with the bank statement had been recorded erroneously in the depositor's accounting records as $372. In preparing the bank reconciliation the appropriate action to correct this error would be to:"

The correct answer to this question is A, add $45 to the balance per the depositor's records. This is because the check was made out for $327 (the company was paying $327 to someone), but they recorded the check, in error, for $372, MORE than the actual amount of the check. Remember that when we write a check, we are giving our money to someone else. So by recording the check for $372, the company took TOO MUCH money out of their cash account. To adjust this, they have to add $45 to their records.

Chapter 7 – Inventory and Cost of Goods Sold

PA7-1 Assuming that for Specific identification method (item 1d) the March 14 sale was selected two-fifths from the beginning inventory and three-fifths from the purchase of January 30. Assume that the sale of August 31 was selected from the remainder of the beginning inventory, with the balance from the purchase of May 1. Where does the 2/5 and 3/5 come in?

What you are trying to do is assign the cost of the inventory sold to Cost of Goods Sold. Under the specific identification method, you are therefore saying exactly which individual items of inventory were sold. So, using the numbers in the book (yours will be different), our calculation of the cost of those items is based on which ones we sold, as follows:

The March 14th sale was for 1,450 units. Two-fifths of those 1,450 units, or 580 units, came from beginning inventory at a cost of $50 = $29,000. The remaining three-fifths, or 870 units (1,450 x 3/5), came from the January 30th purchase at a cost of $62/unit = $53,940. So the cost of the March 14th sale is $29,000 + $53,940 = $82,940.

The August 31st sale was for 1,900 units. Those units came from the remainder of beginning inventory. Beginning inventory was 1,800 units, but we sold 580 of them on March 14th. So the remainder, or 1,220 units, was sold on August 31st at a cost of $50/unit = $61,000. The balance of the sale, or 1,900 - 1,220 = 680 units, came from the May 1st purchase at a cost of $80/unit = $$54,400. So the cost of the August 31st sales is $61,000 + $54,400 = $115,400.

So, Cost of Goods Sold = $82,940 + $115,400 = $198,340

Goods Available for Sale was $341,000, therefore Ending Inventory = $341,000 - $198,340 = $142,660.

Beginning inventory was completely sold. Therefore that $142,660 units in ending inventory represents the remainder of the January 30th and May 1st purchases, as follows:

Jan 30 2,500 units - 870 units sold Mar 14th = 1,630 units @ $62 = $101,060

May 1 1,200 units - 680 units sold Aug 31st = 520 units @ $80 = $41,600

Total = $101,060 + $41,600 = $ 142,660

WHEW!

General guidance for calculating GAS, CGS and EI using a periodic inventory system and LIFO.

The key to this problem is that they are using a periodic inventory system, so they are calculating EI and CGS at the end of the period, not after every transaction. Since you know how many units they started with, plus the number they purchased, so you can calculate Goods Available for Sale in total dollars and number of units.

CGS in units is equal to the number of units they sold, to which you need to assign a cost. The difference between CGS and GAS is the number of units in ending inventory.

Since the system you are calculating is LIFO, you assume that the last goods that came in are the first ones going out as CGS. This is particularly important in periodic LIFO, because you will be taking your costs from the most recent purchase at the end of the month, not the most recent purchase at the time of the sale.

So, to get the value of the number of units in CGS, you start with the last purchase at the end of the month. If that has all of the units you need for CGS, you just take the CGS number and multiply by the unit cost of the purchase. If you need more units, you need to go to the next most recent purchase and take however many more units you need, at the unit cost of that purchase.

This total will be the cost assigned to CGS. The difference between your GAS and CGS is the value assigned to ending inventory.

Why do we need LCM (Lower of Cost or Market)

When the value of inventory falls below its recorded cost (due to identical items being available at a cheaper cost, or because it's become outdated or damaged), then if we do not write it down to it's lower value, we are essentially overstating the value of our inventory. The accounting principle of conservatism says that if doubt exists between two acceptable alternatives (in other words the accountant needs to break a tie), the accountant should choose the alternative that will result in a lesser asset amount and/or a lesser profit. A classic example is inventory where the market value is less than the actual cost. The accountant must decide whether to leave the inventory at cost or to reduce the inventory amount to market. Conservatism directs the accountant to reduce the inventory to the lower amount (market). This results in a lower asset amount and a debit to an income statement account, such as Loss from Reducing Inventory to Market.

Chapter 8 – Receivables, Bad Debt Expense, and Interest Revenue

Why doesn't NRV (Net Realizable Value) of A/R change when you write off an account?

When you write off an uncollectible account, you decrease your business's total assets because an uncollectible account is money a customer owes you that you will not collect. Using the allowance method, when you set up the allowances account, you decrease assets. When you journalize an uncollectible account, you decrease an asset and contra asset; these entries cancel each other resulting in no change to assets.

Assigned Problem P8-5, Question 2

Some people are getting stuck on question 2 on P8-5. Please make sure you are calculating average receivables using the NET receivables numbers ("Accounts Receivable, Net of Allowance") in your calculation. If you use the gross receivable (accounts receivable before deduction of the allowance), it will be marked incorrect.

Chapter 9 – Long-Lived Tangible and Intangible Assets

Are patents the only thing amortized (on this test at least) and are they amortized through straight-line amortization? If that is the case, is the formula: COST/ESTIMATED USEFUL LIFE?

All intangible assets are amortized, except those that have an infinite or indefinite life (goodwill and trademarks). And yes, they generally don’t have residual values and are always amortized using the straight-line method, so COST/EUL.

Chapter 10 – Liabilities

"Bondholders" are the investors who buy the bonds.. To them, the bond is an investment and would show on their balance sheet as an asset.

The "Bond Issuer," or seller, is the company issuing/selling the bonds in order to borrow a large amount of money. To them, the bond is a long-term liability (depending on the maturity date).

Assigned Problem PA10-7, requirement 4 and 5.

A common problem with bond pricing and the effective interest method is rounding. $0.44 here and $0.39 there eventually result in missing dollars.

In this problem, the narrative says "Surreal uses the effective-interest bond amortization method and adjusts for any rounding errors when recording interest in the final year."

Thus, when you get to the last (third) interest payment and journal entry, you need to make sure that your interest expense and discount amortization are equal to an amount that brings the discount to zero. For example, you might have the following:

Discount on issue in the amount of $36,072

Interest journal entry 1: discount amortized of $11,558, discount balance now $24,514

Interest journal entry 2: discount amortized of $12,020, discount balance now $12,494

To complicate the issue further, the solution allows a margin of error of +/-4 on the interest expense entry, but NOT on the "loss on bond retirement" (which should be the same number as interest expense) and NOT on the "discount on bonds payable" amounts, which should all be the remainder of the discount balance.

Assigned Problem PA10-7, requirement 4

Note that the 12/31/2020 entry is what would be entered if the bonds were retired at maturity. The cash amount would therefore be the face value of the bonds plus the last interest payment.

Assigned Problem PA10-7, requirement 5

Note that the 12/31/2020 entry assumes that the company holds the bonds until maturity. The 1/1/20 entry assumes, instead, that the bonds are retired a year earlier at 102. So you have to zero out the discount (in the same manner you did for the 12/31/20 entry), then the difference is your loss on retirement.

Chapter 12 – Statement of Cash Flows

When are stocks and bonds considered financing activities, versus investing activities?

Stocks or bonds are financing activities when they are those stocks and bonds issued by the company itself, whether they are issuing them or buying them back. Stocks or bonds are investing activities when they are those stocks and bonds purchased (as an investment) from other companies.

Practice Exam 2, Chapters 4, 5 and 6

Number 14 on the practice exam, why is the answer A and not D? The equipment was used for one year and 9 months. The one year would be 3,000 and the nine months would be 2,250 so for the full year and nine months the depreciation is 5,250 at the end of December 31, 2017. And since it's an expense wouldn't it be debited as 5,250 depreciation expense?

Depreciation expanse always represents ONLY the 12 months of expense for that given year. The $2,250 represents the depreciation on the equipment for 2016. The question is asking for the adjusting entry for 2017. Notice that the accumulated depreciation balance is $2,250. That is because in 2016, the company's year-end adjusting entry was for nine months of the year, as follows.

Depreciation Expense 2,250

Accumulated Depreciation 2,250

So in 2017, we've had the equipment for a full year, so we need to record 12 months of expense:

Depreciation Expense 3,000

Accumulated Depreciation 3,000

Now the ending balance in accumulated depreciation will be $5,520, representing a full year and nine months.

We will never book more than 12 months of depreciation expense in a year. If we did, our depreciation expense would be overstated for the year. If we had, in fact, not booked the expense last year, it would have to be booked as a prior year adjustment, which causes ALL SORTS of accounting issues which you don't even want to think about right now! 🙂